cloudspotter

[음식우표] 페로 제도 2005 - 전통음식 본문

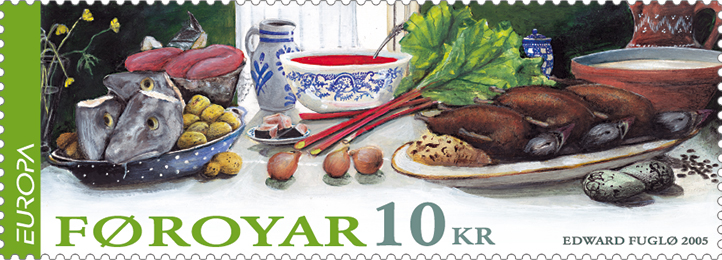

▲ 페로 제도의 여름철 전통음식.

왼쪽부터 대구cod 머리, 감자, 대구 곤이 (암컷의 난소roe), 샬롯,

루바브, 속 채운 퍼핀 (puffins 펭귄처럼 생긴 귀여운 바닷새), 퍼핀 알.

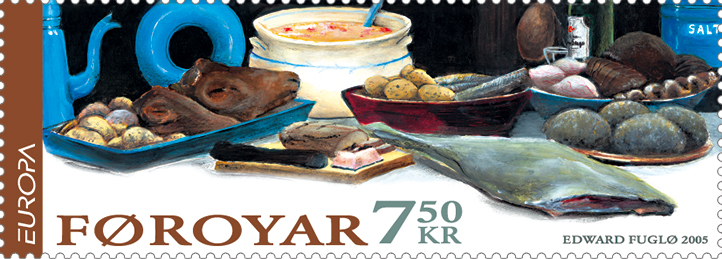

▲ 페로 제도의 겨울철 전통음식.

왼쪽부터 스위드, 양 머릿고기, 말린 고래고기 (도마 위 검은색 고기),

말린 고래지방 (그 옆 분홍색), 말린 양고기skerpikjøt.

우표 크기 72×26mm. 'Europa 2005 Gastronomy' 참가작.

▲ 페로 제도의 예약제 가정집 식당들이 흔히 낸다는 전통음식 플라터platter.

[☞ faroeguide.fo]

시계 방향으로, 삶은 감자, 말린 양고기를 얹은 호밀빵, 말린 흰살생선,

말린 고래지방(분홍색), 말린 고래고기(검은색).

먹을 게 얼마나 없었으면 바닷새와 고래까지 다 잡아 먹었겠나.

먹거리가 넘치는 21세기에 웬 고래잡이냐며 동물보호단체들 아우성인데,

동물권이고 생태·환경이고 뭐고,

나는 덩치 큰 생선은 일단 중금속이 염려돼 못 먹것다.

2005년, 유럽 각국의 우정국들이 자국의 전통음식을 담은 우표를 발행하기로 의기투합, 손바닥 면적의 5분의 1도 안 되는 작은 종잇조각에 그 많은 유럽 국가들의 식문화가 깨알같이 담기게 되었습니다. 단단 같은 음식우표 수집가들한테는 꿈 같은 행사였죠. 이때 발행된 우표들을 거의 다 소장하고 있습니다.

오늘은 아이슬란드와 노르웨이 사이에 있는 페로 제도Faroe Islands의 전통음식들을 살펴봅니다. (저 작은 우표에도 그림 그린 사람 이름 떠억 박아 놓은 것 좀 보세요. 창작자를 꼭 밝히고 기리는 습관, 한국도 본받아야 합니다.)

아래의 글은 페로 제도의 우정국이 발행 당시 제공했던 정보입니다. 작은 제도가 번듯한 소개글에 영어 번역까지 제공을 했어요. 이러면 또 낯선 식문화에 대해 애먹으며 자료 조사할 필요가 없어 단단은 감격합니다. 귀차니스트의 발번역 나갑니다.

페로 제도의 식문화

All over the world the provision and preparation of food have always been an important part of national culture, with countless variations being shaped by the possibilities to hand.

세계 어디서든 식량의 공급과 준비는 한 국가의 문화적 정체성에 중요한 부분을 차지해 왔습니다. 주변에서 쉽게 구할 수 있는 재료가 무엇이냐에 따라 변주가 일어나기도 하고요.

Climate has been crucial in terms of the type of food it was possible to produce. Living in tropical countries and having to survive in the polar regions will always be different, of course.

기후는 식량 생산에 결정적인 역할을 하므로 열대 지역의 음식과 극지대의 음식은 당연히 다를 수밖에 없겠죠?

The original food on the Faroes came for the most part from the animal population on the island, mainly sheep in the upland pastures, birds on the bird cliffs and fish in the sea. The climate is not the best for cultivating cereals, vegetables, etc., so they were not of great importance.

페로 제도의 식문화는 식물보다는 동물들로부터 얻은 것들이 많습니다. 그중 고원의 풀을 뜯고 사는 양羊들과, 해안가 절벽의 바닷새들, 그리고 주변 바다로부터 나는 해산물이 주요 자원이 되었습니다. 여기 기후가 곡물, 채소 등의 경작에는 맞지 않아 이것들은 뭐 언급할 건덕지가 없습니다.

Potatoes did not become a regular ingredient in the daily diet until the late 19th century, although people had long been familiar with them. Instead they used to boil Faroese swedes (Brassica) for dinner, for example.

감자는 19세기 후반이 되어서야 페로 제도의 일상 식재료로 자리잡게 되고 그 전까지는 이곳 땅에서 나던 스위드를 삶아 먹었습니다.

The seasons set their stamp on eating habits. Fish was more or less available all year round, but mostly in the spring, when it provided roe in addition to liver. The opportunity to eat other fresh food arrived at the same time as spring fishing (March – April). Cows usually calved in spring, so there was most milk in summer. Birding and egg collecting (nest plundering on the bird cliffs) were also part of the summer, while the chances of catching pilot whales are greatest in August, when people could also go out into the potato fields and pick new potatoes. In autumn the men went up into the mountains to bring the sheep in for slaughtering. Nearly every bit of a slaughtered sheep was put to good use. As well as the meat, people used the head, trotters, liver, lungs, heart, stomach and blood (the collective Faroese word for which is avroð).

계절의 변화에 따라 식습관이 달라집니다. 생선은 일년 내내 잡을 수 있으나 봄에 잡은 생선에서는 곤이와 이리, 간까지 즐길 수 있습니다. 이때는 다른 신선한 재료들도 납니다. 소가 이맘때쯤 새끼를 낳으므로 여름에는 우유를 얻을 수 있고, 해안가 절벽에서의 새잡이와 새알 모으기도 여름에 합니다. 검은고래잡이와 햇감자 수확은 8월에 합니다. 가을에는 산에 있던 양을 데리고 내려와 도축합니다. 양 한 마리를 도축하면 살코기뿐 아니라 머릿고기, 족, 간, 허파, 심장, 위 등의 부속과 선지까지 알뜰히 사용합니다.

Since ancient times the only way to keep most foodstuffs was to salt or dry them. Salt was in short supply for a long time, so drying was the commonest method for preserving food. There were two salting methods, pickling in brine and dry-curing, with barrels being used for both.

예로부터 식재료의 저장은 염장과 건조를 통해서만 가능했습니다. 페로 제도에서는 오랫동안 충분한 양의 소금을 얻을 수 없었기에 건조가 가장 흔한 저장법이 되었습니다. 염장은 수염이나 건염, 이 두 가지 방법을 쓰고 나무 원통을 사용했습니다.

Meat, whale, fowl and fish were all dried. Once gutted, sheep were hung up to dry in the wind in a single piece. Before birds were hung up, they were split along the back and tied together in pairs. Fish too were hung up to dry in pairs, while whale meat was cut into loops before hanging.

적색육, 고래고기, 가금류, 생선은 모두 건조법을 써서 저장했습니다. 양은 내장을 제거한 뒤 통풍 잘 되는 곳에 통째로 매달아 말리고, 가금류와 생선은 반 가른 뒤 한 쌍이 되도록 묶어 매달아 말리며, 고래고기는 적당한 크기로 포 뜬 살의 끝부분 중앙에 짧게 칼집을 하나 내어 그 부분을 손잡이처럼 이용해 걸어 말립니다.

The autumn weather had a major impact on whether what had been hung up to dry tasted right. The drying process itself can be divided into three stages: visnað (lightly dried), ræst (semi-dried/seasoned) and dried. These terms refer to flavour, appearance and smell. What we can call “lightly dried” is achieved in just a few days and is much faster for fish than for whale meat. The word visnað is not generally used about meat.

가을 날씨는 건조 숙성 식품들의 맛이 제대로 들게끔 하는 데 중요합니다. 건조 식품은 세 단계로 나뉘며 단계에 따라 맛, 외형, 향이 달라집니다.

(1) 단 며칠 동안만 말려 살짝 건조시킨 것 (visnað)

일반 생선이 고래고기 포 뜬 것보다는 훨씬 빨리 건조되며 육지동물의 적색육에는 단기 건조법을 여간해선 쓰지 않습니다.

The change to ræst is slow, but if the air suddenly turns cold, whatever has been hung up to dry can jump this stage and never gets the real semi-dried/seasoned flavour. If, on the other hand, the air is too warm, the dried meat can become too ræst and so end up with a harsh or rank flavour. Meat is normally dried until Christmas.

(2) 반건조한 것 (ræst)

살짝 건조한 단계에서 반건조 단계가 되기까지는 시간이 제법 걸립니다. 그러나 공기가 갑자기 차가워지면 제대로 된 반건조 풍미를 내지 못 하게 되고, 반대로 공기가 지나치게 따뜻해져도 너무 말라 버려 고약한 맛을 내게 됩니다. 육지동물의 적색육은 대개 크리스마스 전까지 건조시킵니다.

Mutton, fish, fowl and whale meat are eaten at all three stages of the process (and fresh too, of course). Visnað and ræst have to be cooked. Dried meat is eaten as it is. For food to have the best possible flavour, it has to be treated correctly, of course. In particular you have to make sure that flies are kept away, especially in mild autumn weather, or there is a risk of the food being spoiled by maggots.

(3) 완전건조한 것 (turrur)

양고기, 생선, 가금류, 고래고기는 생물 상태뿐 아니라 살짝 건조, 반건조, 완전건조, 각 세 단계의 것을 모두 먹습니다.

살짝 건조시킨 것과 반건조시킨 것은 익혀 먹어야 하고, 완전건조시킨 것은 그냥 먹습니다. 최상의 맛을 얻기 위해서는 당연히 재료를 신경 써서 다루어야 하는데, 온화한 가을 날씨에는 특히 파리가 꼬여서 구더기가 생기지 않도록 주의해야 합니다.

Mealtimes vary from country to country. In days gone by there were three main mealtimes on the Faroe Islands: morgunmatur (lunch) at around 9–10 am, døgurði (dinner) at around 2–3 pm and nátturði (supper) at 9 pm or later. Normally there were also two smaller mealtimes: ábit (breakfast), which people ate when they got up early in the morning, and millummáli (tea), which came between dinner and supper.

나라마다 식사 시간이 다를 텐데, 과거 페로 제도에서는 하루 세 번의 식사 시간을 가졌었습니다.

(1) 오전 9-10시경 이른 점심식사

(2) 오후 2-3경 정찬

(3) 밤 9시나 그 이후 저녁식사

보통 여기에 두 번의 조촐한 취식 시간까지 더해져, 이른 아침 일어났을 경우 간단한 아침식사를, 점심식사와 저녁식사 사이에 간단한 찻자리를 가졌습니다.

For lunch people used to eat drýlur (cylindrical, unleavened bread, originally baked in the embers of the fire). Later, rye bread made from rye and wheat flour became more common. An accompaniment would be served with the unleavened bread. These days it is sliced meats and the like, but back then it was most likely to be a piece of mutton.

이른 점심식사로는 오븐의 잔열에 구운, 효모 넣고 부풀리지 않은 원통형의 빵 'drýlur'를 먹었었는데 이는 점차 호밀과 밀을 섞어 만든 빵으로 대체되었고, 요즘은 얇게 저민 고기를 곁들이지만 예전에는 양고기를 먹었습니다.

Dinner usually consisted of boiled fish, whale meat and blubber or fowl. In the late 19th century it became common for people to eat potatoes for dinner. On Sundays and festivals those who could (i.e. farmers) would have ræst meat and súpan – soup, specifically meat soup (made from preserved meat with flour or grains, etc., added). Cooked fish was also considered to be a good Sunday meal.

정찬은 삶은 생선, 고래고기와 고래지방, 또는 가금류로 구성되었습니다. 19세기 후반에는 감자를 먹는 일이 흔해졌습니다. 일요일이나 명절에는 반건조육과, 저장육에 밀가루나 곡류 등을 넣은 고기 수프를 먹는 사람들도 있었습니다. 익힌 생선 역시 일요일에 먹기 좋은 음식으로 여겼습니다.

Supper nearly always took the form of spoon food, i.e. milk products of various sorts in summer and soup in winter. When the cow had calved there would be ketilost, a cold dish of heat-thickened colostrum served with cinnamon and sugar. Drýlur and bread were not eaten with supper, but it was common to eat wind-dried fish before the soup. People generally drank water, milk, milk mixed with water, tea or coffee.

저녁식사는 여름에는 다양한 유제품류, 겨울에는 수프 등 거의 항상 숟가락으로 떠먹는 음식들로 구성되었습니다. 소가 새끼를 낳는 계절에는 시나몬과 설탕을 뿌린 라이스 푸딩을 먹었으며, 빵은 저녁식사 때는 내지 않아 수프를 먹기 전에는 빵 대신 건조 생선을 먹었습니다. 마실거리로는 물, 우유, 우유 혼합 음료, 차, 커피 등을 냈습니다.

No one started the day’s work on an empty stomach. Breakfast was therefore a slice of drýlur and a drink of milk, a little soup or leftovers from the previous day’s supper.

페로 제도에서는 아무도 위장이 빈 상태로 일을 시작하지 않았습니다. 아침식사로는 위에서 언급한 부풀리지 않은 전통빵, 우유, 수프 소량, 또는 전날 저녁식사 때 먹고 남긴 음식을 먹었습니다.

For tea people drank milk, tea or coffee accompanied by a slice of bread or, occasionally, pancakes. White bread or cake has gradually become more common.

찻자리에서는 우유, 차, 커피 등을 빵이나 팬케이크를 곁들여 먹곤 했는데 백밀빵이나 케이크 등도 점차 흔히 볼 수 있게 되었습니다.

Food was generally boiled. Every household had at least two pots: one for oily or greasy food such as blubber, liver, etc., and one for everything else. There were three types of food bowl: a meat bowl, a fish bowl and a snyktrog (for greasy or oily food). As well as their pots, people also kept large ladles (sleiv), slotted spoons (soðspón) and various “sticks” for stirring porridge (greytarsneis) and whipping milk or cream (a milk beater or tyril) in their one-roomed hut, which served as kitchen, workshop, living room and bedroom.

'삶기'는 페로 제도의 주된 조리법으로, 각 가정은 최소 두 개의 솥을 두고 썼는데, 하나는 고래지방이나 동물의 간 같은 기름진 식재료용, 다른 하나는 다목적용이었습니다. 그릇은 고기용, 생선용, 기름진 음식용, 세 가지를 씁니다. 큰 국자와 구멍 뚫린 스푼, 그리고 죽이나 우유를 젓거나 크림을 거품 내기 위한 여러 형태의 막대들도 단칸 오두막의 주방의 주요 조리도구입니다. 이 단칸 오두막은 부엌으로도, 작업실로도, 거실로도, 침실로도 쓰였습니다.

Times have changed, with the result that we now eat a lot of food bought in shopping centres – most of it foreign. The Faroe islanders have acquired an international cuisine, with vegetables, fruit and spices being a normal part of everyday life. But old Faroese food is still eaten with great relish and is regarded as a real delicacy.

시간이 지나면서 외국 음식들로 외식하는 일이 잦아졌고 채소, 과일, 향신료 등을 쓴 외국 음식들을 쉽게 접할 수 있게 되었으나 페로 제도의 전통음식들은 여전히 별미로 사랑 받고 있습니다. ■

'음식우표' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 추억의 음식, 파르페 (+ 과일 빙수, 선데이, 이튼 메스, 탕후루, 트라이플) (9) | 2023.05.14 |

|---|---|

| [음식우표] 일본 2021 - 나고야 대표 음식 ① 히츠마부시 (ひつまぶし) (11) | 2023.05.04 |

| [음식우표] 대한민국 1993 - 버섯 시리즈 - 표고 (17) | 2022.08.21 |

| [음식우표] 페로 제도 2010 - 뿌리채소 (감자, 스위드) (7) | 2022.06.06 |

| [음식우표] 덴마크 2012 - 오픈 샌드위치 스뫼레브뢰드 슈뫼어브롣 (Smørrebrød) (4) | 2022.05.27 |

| [음식우표] 일본 2015 - 라멘 Ramen (8) | 2022.04.15 |

| [음식우표] 우크라이나 2005 - 보르쉬, 보르쉬츠 (borsch, борщ) 비트 수프 (9) | 2022.02.28 |

| [음식우표] 대한민국 2003 - 한국의 전통음식, 약과 (8) | 2022.02.03 |